Spain is no exception. Major European countries do not have specific regulations regarding election debates during campaigns. The media regulate it at their sole discretion and neither in Italy, France, Germany nor the UK is obligated to do so. Candidates accept or reject them according to their own interests.

Italy has no regulations setting norms, times or obligations for candidates to attend debates during political campaigns. The genre, which has seen a sharp decline in recent years, had its splendor in the late nineties, …

Subscribe to continue reading

Unlimited reading

Spain is no exception. Major European countries do not have specific regulations regarding election debates during campaigns. The media regulate it at their sole discretion and neither in Italy, France, Germany nor the UK is obligated to do so. Candidates accept or reject them according to their own interests.

Italy has no regulations setting norms, times or obligations for candidates to attend debates during political campaigns. The genre, which has seen a sharp decline in recent years, had its heyday in the late nineties, coinciding with the disruption in Silvio Berlusconi’s political scene. Dialectical battle between Il Cavaliere and Massimo D’Alema on public television before journalist Enrico Mentana (even immortalized by Nanni Moretti in his film April). Those were the golden years. Recent election campaigns, however, enjoyed few minutes of the genre, sponsored only by a few newspapers such as Il Corriere della Sera, and mainly ignored by viewers.

In France, electoral debates are a democratic ritual, but the law does not require them to be held. The debate par excellence, and what focused all the attention and audience, was the second round of the presidential election, between two secret candidates fighting for the keys to the Elysee. It has been held since 1974, when Valéry Giscard D’Estaing and François Mitterrand met. In 2002, the then president, Jacques Chirac, broke this tradition for the first and only time by refusing to debate right-winger Jean-Marie Le Pen, who qualified for the second round. In 2017, debates were also held between the candidates for the first round, but Emmanuel Macron refused to participate in these debates in 2022, when he faces re-election, justifying this by saying that no sitting president has done so. The debate was not held and, instead, a special program was broadcast with interviews with the candidates… including Macron. The second round of debate was hosted by TF1 (private) and France 2 (public), the two main channels.

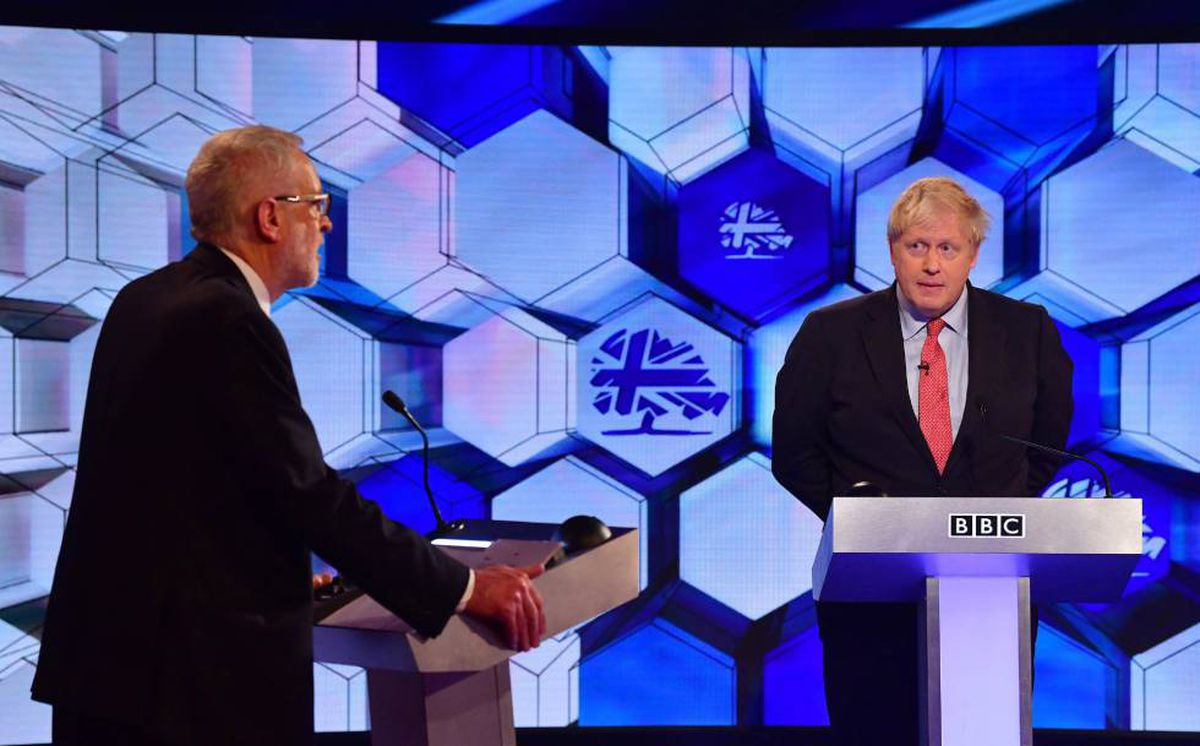

The United Kingdom has televised electoral debates on at least four campaigns: 2010, 2015, 2017 and 2019. This past year, two face-to-face debates were scheduled between the two main candidates, conservative and then-leader Boris Johnson. from Labor opposition Jeremy Corbyn. The first, held on the private network ITV, had nearly seven million viewers. The second, which took place on public Channel 4, was ultimately canceled due to Johnson stepping down. However, there are no laws that enforce or regulate debate. The general consensus is that this is a matter that must be agreed upon between the various political parties and the media, public or private, that aspire to host these electoral acts. As in other countries, this uncertainty leads to the interests, needs or strategies of each formation which condition the final negotiations or format. In 1997, for example, Conservative Prime Minister John Major, aware of the unstoppable tide of popularity that Tony Blair was riding, desperately tried to force a fight that never happened.

In 2010 three debates were held, which included Liberal Democrat Nick Clegg, along with Tory candidate David Cameron and Labor Party candidate Gordon Brown. The media hosting the clashes were the BBC, ITV and prominent figure Rupert Murdoch’s channel BSkyB. The election resulted in the first coalition government in Downing Street, between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats. Despite the fact that polls have not failed to demonstrate the importance British voters attribute to this televised debate, there is still a deep desire in the UK for the kind of campaigning that is done door-to-door and close to the electorate. In a parliamentary system, it is the individual candidate who has to fight for his own seat in his constituency, and celebrates tradition hasting, private meetings with their constituents to address their complaints and requests and uncover the merits of the electoral programme.

Election debates are also not regulated in Germany. The number and format are agreed between the television channels, public and private, and the parties. Usually one or two debates take place, and only between candidates from the two main formations, the SPD and CSU. Therefore they meet face to face, summoned duel (duel). However, in the last election (September 2021) this changed for the first time, as three candidates for chancellor faced each other: the Social Democrat (Olaf Scholz), the Christian Democrat (Armin Laschet) and the nominee of the Greens, Annalena Baerbock. Additionally there were three debates, on three consecutive Sundays.

What affects the most is what happens closer. To not miss anything, subscribe.

subscriber

Other parties with representation in the Bundestag, the German Parliament, engage in secondary debate among themselves, usually one or two. All formations are invited, including the far right, which has had parliamentary groups since the 2017 election. However, at the last election, public television hosted a sort of final debate with seven candidates, three days before the election, one for each formation represented. in Parliament. And all parties brought their first swords. So there are actually four debates and four opportunities to see the potential chancellor defend their proposal. The first was held on RTL and n-tv (private); the second, in ZDF and ARD (public); the third, on ProSieben, Sat.1 and Cable eins (private); and the fourth, with 7 candidates, in public ZDF and ARD.

“Web specialist. Incurable twitteraholic. Explorer. Organizer. Internet nerd. Avid student.”