In 2016, James Vlahos learned that his father was dying of terminal lung cancer.

Painfully realizing that their time together was running out, Vlahos scrambled to collect memories while he still could, recording his father’s life story; from childhood memories to your favorite sayings, songs and jokes.

Once transcribed, this recording fills 200 pages.

“It was a great resource, but it was laggy, and I missed something interactive. So I spent almost a year programming a replica of my dad in chatbot form: ‘Dadbot,’” explains Vlahos.

This “Dadbot” is able to relive his father’s story through text, audio, image and video messages, creating interactive experiences that mimic the unique nuances of an individual; Father Vlahos.

While this artificial version could never replace Vlahos’ biological father, it did provide comfort and a way to remember him after death.

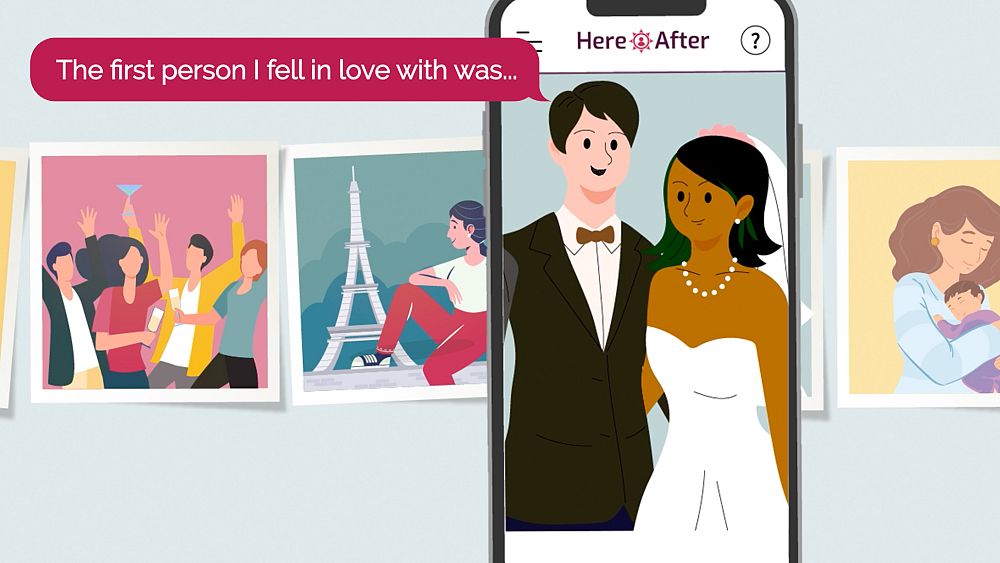

It also inspired Vlahos to create HereAfter AI, a US-based company that allows people to upload their memories, which then become “life avatars” that friends and family can communicate with.

Unlike dusty photo albums or inactive Facebook profiles, this is a way of archiving parts of ourselves or loved ones that can be brought back to life.

digital immortality

Loss is one of the most difficult human experiences to live with, and coping with it is even more difficult in the digital age: snippets of conversations are forever archived in Whatsapp chats, Instagram pictures, recent tweets, and Facebook’s memories feature.

For some, being able to revisit online archives of people they have lost is comforting.

In 2021, a writer named Sherri Turner went viral after tweeting that she had seen her mother’s house on Google Maps Street View, going back to 2009: “There’s a light in her bedroom. It’s still her house, she’s still alive.” “.

Others have dabbled in more advanced technology in an attempt to bring the dead back to life, such as freelance writer Joshua Barbeau, who — as documented in a 2021 San Francisco Chronicle article — trained an artificial intelligence chatbot on a website called Project December to pose as his fiancee. is dead, Jessica.

But there isn’t much that can be done with a person’s digital remains, their social media profiles being portals to nostalgia, but are ultimately empty and flat; an empty house frozen in time.

“We share a lot of ourselves on social media, but a lot of the time it’s very concrete bits and pieces, it’s not the same process as if you sat down with your personal biographer, stepped into your life and shared what made you be that person. you,” explained Vlahos to Euronews Next.

Instead of using the digital footprints people leave behind – and all the ethical dilemmas that arise – the HereAfter AI model is based solely on user consent, who must choose to be interviewed and can choose who they share information with. historical avatars”.

“For our app specifically, we want it to be accurate and honest. We can’t allow AI to make things up that aren’t true for the real person, because that could be a horrific and misleading experience for family members later on, Vlahos explains.

Response to the app has been positive so far, with users deeply moved to hear their loved ones’ voices again, and some even discovering stories about their parents they had never heard of before.

“Their ability to bring families closer together or uncover information that doesn’t appear in everyday conversation can be very meaningful and useful to people.”

The future of “dueling technology

Preserving memories and passing on heirlooms is an innate human desire that manifests in everything from ancient artifacts to architecture, so it’s no surprise that technology companies are looking for new ways to advance and improve these processes.

Last year, an 87-year-old woman attended her own funeral in England thanks to a startup called StoryFile, which – similar to AI HereAfter – records images and audio before someone’s death and then renders them interactive. AI and holographic avatars.

In particular, the explosion of ChatGPT, a powerful chatbot created by OpenAI, has accelerated the development of other “grief technologies”, including its integration into the “live forever” metaverse, a project by Somnium Space company that hopes to create a digital “you” that can live forever. within the metaverse (a concept that hasn’t been fully defined yet).

In its current form, HereAfter’s AI technology is strictly based on capturing things people have recorded, but in the future it hopes to use powerful language models such as ChatGPT to improve its conversational capabilities, except that it is still limited to the information it provides.

“I won’t be able to speak freely about so many things, but I also have limited knowledge not to go looking for random information on the Internet.”

Technology is also not limited to grief and loss. It can be used in the moment, to document personal thoughts or communicate difficult conversations and secrets.

“This can be useful while people are alive, you don’t have to die for your avatar to be useful,” says Vlahos.

Is this a healthy survival mechanism for us?

While it’s true that these AI avatars can be useful for the grieving process, providing soothing balm during turbulent times, there’s also the risk that they’ll leave us clinging to the past, unable to move forward and develop.

“Several studies have demonstrated that proximity seeking [comportamientos dirigidos a restablecer la cercanía con la persona fallecida] associated with worse mental health outcomes,” Dr. Kirsten Smith, a clinical researcher at the University of Oxford, told Euronews Next.

“Close-seeking behavior can prevent a person from forging a new identity without the deceased or from building new meaningful relationships. It can also be a way of escaping the fact that the person has died, a key factor in coping with loss.”, says .

As with everything in life, moderation is key, and storing memories to look back on, whether they be physical objects or digital avatars, is harmless in and of itself; it is the frequency and intensity of our dealings with them that can cause problems.

“We all want to feel close to our loved ones after they die, and if this technology proves harmless in well-controlled empirical studies, it could be an interesting way to remember our loved ones.”

Vlahos also questions whether the fear that this type of technology will keep people from advancing is completely justified.

“I don’t think moving on means having to forget someone or letting that person’s memories fade and become boring. So if there’s a way to have a richer, more present, high-fidelity memory from someone, I think that’s a positive thing,” she says.

Wherever this technology may take us, living or dead, perhaps most importantly it is a reminder to take advantage of the fragile and fleeting gifts with those we love, before we turn to dust and pixels.

“Entrepreneur. Internet fanatic. Certified zombie scholar. Friendly troublemaker. Bacon expert.”