How long will British MPs tolerate the fact that there are at least 119 MPs from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland carrying out important, possibly decisive, work? its impact on British politics when they themselves have no say in the same affairs in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland? This was the question posed by the Scottish Labor MP, Tam Dalyell, from the West Lohtian district of Scotland, in 1977 in the Westminster Parliament in a debate on the level of self-government…

Register for free to continue reading on Cinco Dias

If you have an account with EL PAÍS, you can use it to identify yourself

How long will British MPs tolerate the fact that there are at least 119 MPs from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland carrying out important, possibly decisive, duties? its impact on British politics when they themselves have no say in the same affairs in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland? This was the question posed by Scottish Labor MP Tam Dalyell, from the West Lohtian district of Scotland, in 1977 in the Westminster Parliament in a debate on the extent of self-government in non-English areas of England.

Is it not relevant to answer the question, by changing the term of office, regarding the capacity that the nationalist deputies in Spain have in general matters, while other deputies do not have the prerogative of transferred powers within a particular autonomous community? How much sense does it make for the deputies of the Basque Nationalist Party, EH Bildu or even the Navarro People’s Union to vote on a decisive regulation regarding the design and development of the Spanish Personal Income Tax, if it does not affect them, while not being able to have deputies from all of Spain decide on the tax the same in the Basque Country and Navarra?

In several governments during the Spanish Transition, nationalist deputies were crucial to the smooth running of government, both in the Basque and Catalan regions, sometimes even in the Canary Islands, and among both right-wing and left-wing executives. And they do this with a double degree of power due to the two conditions that they demand significant contributions in return for their timely support, and to decide on issues that in their territory they are beyond the influence of the national Parliament, and even many times even beyond the powers of the State Government.

The debate regarding the level of power and influence of parliament in Spain has never been open, but in other countries with regional structures, this has occurred, although it has not yet been definitively resolved. In the United Kingdom, debate arose in the late 19th century regarding the law of Irish self-government, although debate had raged in previous decades regarding the coexistence of England and Scotland under the same crown and with two Parliaments. However a more recent issue emerged in 1977 which called into question the dual empowerment of Scottish seats in the national Parliament.

A large number of countries have limited the power of minority groups, whether nationalist or not, to avoid further pressure on majority groups in the elaboration of norms, or even in the formation of parliamentary majorities. An obvious tool to do this is an electoral law with minimum requirements for winning seats, but in Spain this is only a demand that emerged in the last decade due to the impossibility of forming a coherent parliamentary majority.

Bearing in mind that Spain has no such borders and is not a federal state, although the communities that make it up have, some of them, more than enough power to consider these matters, the final decisions regarding most matters of political management when this occurs, some types of gaps remain in the hands of the central government, although on many occasions they end up subject to legal interpretation by the courts.

However, in matters requiring the transfer of powers as stipulated in the autonomy law, regional sovereignty is already full and the authority of national institutions to make decisions is practically non-existent. In fact, any conflict that the central government attempts to resolve through a corrective regulation or decision is interpreted by local governments, especially if the conflict is in the hands of nationalists, as an attack on their own government, if not. essentially national.

In cases where regional governments have legal powers, the Executive of Madrid has little or no say, and the Congress of Deputies has no say whatsoever. However, deputies from regions with high standards of self-government retain the ability to legislate on the same issues in other regions of the country. The most eminent paradigmatic example is the capacity possessed by the nationalist deputies in the Basque Country and Navarra (PNA, EH-Bildu and UPN) to prepare and vote on the State Budget and all the taxes that form part of their revenues, even though none of them represent that country. Both the Basque Country and Navarre are part of the general taxation regime, as they have their own taxes and related administrative apparatus for levying them. The same thing also happens to other authorities they have, be it police, health or education.

In the case of general powers, it is surprising, but not unusual, that explicitly pro-independence parties claim for themselves, like a closed territory, power and authority over them, and want to rule and legislate over them. they are in national territory. This was a common behavior among all radical nationalists (Basques, Catalans, Galicians and new Valencians), without representing the regions where they lacked seats. In fact, such boldness reaches the point of wanting to intervene in the Administration of other autonomous communities in the transfer of power, as is the case with most of the taxation decisions that have been implemented by the liberal regional governments in Madrid, Andalusia, Galicia or Valencia. Community. .

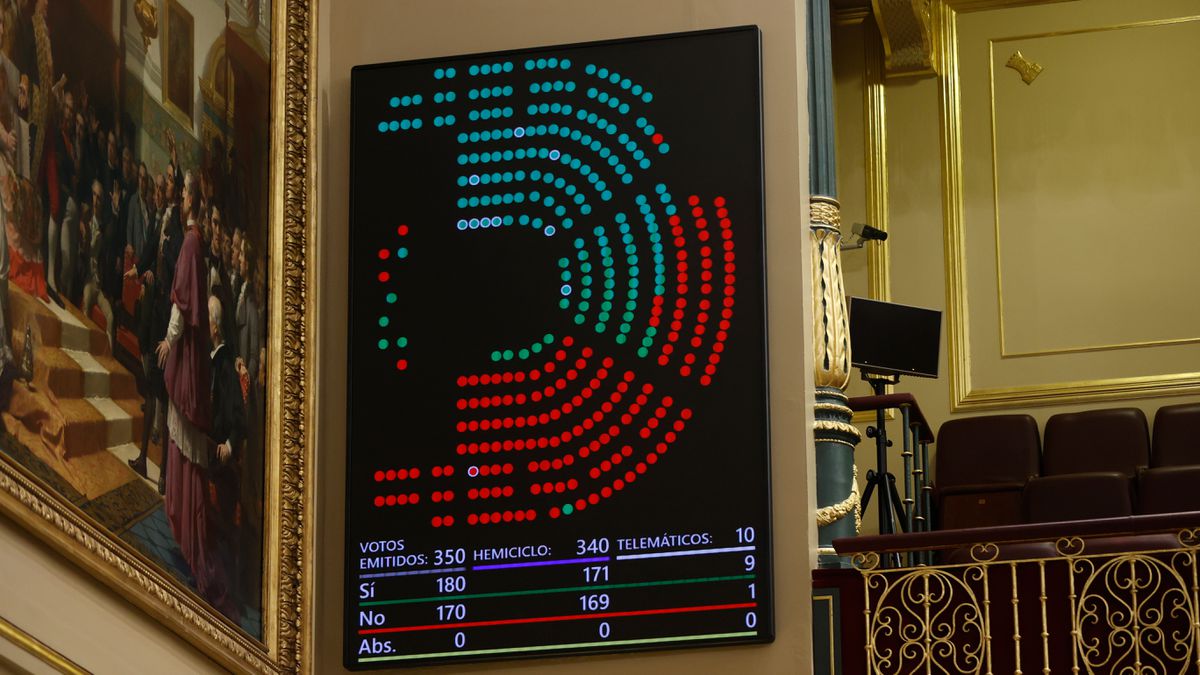

By the way: the deputies of JunsxCat and Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya could of course vote in favor of Pedro Sánchez’s coronation. But can they vote for the amnesty law they themselves demand? a must for coronation, even though those who are given amnesty are the leaders themselves and cadres who meet the requirements? Should Parliament allow them to vote in what they consider to be a self-amnesty? Wouldn’t it be reasonable to demand that they, as political representatives, show the courtesy of not appearing in such situations, as every business or political leader does in matters involving conflicts of interest in which they are in no way able to be judges and parties. ? Could the Catalan nationalist deputies decide, with added ridicule, on a debt forgiveness that benefits only their voters, so that it can be financed by other Spanish taxpayers?

Jose Antonio Vega he is a journalist

Follow all the information Five days in the Facebook, X And LinkedInor in our newsletter Five Day Agenda

“Web specialist. Incurable twitteraholic. Explorer. Organizer. Internet nerd. Avid student.”